The linguistic diversity of our species is under extreme stress, as are the communities who speak increasingly endangered speech forms. Of the world’s living languages, currently numbering around 7,000, around half will cease to be spoken as everyday vernaculars by the end of this century.

For communities around the world, local languages function as vehicles for the transmission of unique traditional knowledge and cultural heritage that become threatened when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted. As globalisation and rapid socio-economic change exert complex pressures on smaller communities, cultural and linguistic diversity is being transformed through assimilation to more dominant ways of life.

In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages to help promote and protect Indigenous languages. This celebration of linguistic vitality and resilience is welcome, but is it enough? And in an increasingly and often uncomfortably interconnected world, what is the role for the ‘heritage’ languages that migrants bring with them when they move and settle in new places?

In this richly illustrated lecture, I will draw on contemporary examples from North America, Asia and Europe to explore the enduring importance and compelling value of linguistic diversity in the 21st century.

Dr. Mark Turin is an Associate Professor of Anthropology and First Nations Languages at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Trained in anthropology and linguistics, he has worked in collaborative partnership with Indigenous peoples in the Himalayas for over 20 years and more recently with First Nations communities in the Pacific Northwest. He is a committed advocate for the enduring role of Indigenous and minority languages, online, in print and on air through his BBC radio series.

If you wish to attend this event, please RSVP here on Eventbrite

March 06, 2019 at 7:00pm

Italian Cultural Centre - Museum & Art Gallery - (3075 Slocan St, Vancouver, BC V5M 3E4)

Event Follow-up

A Caption of Dr. Mark Turin’s “Rising Voices: Linguistic Diversity in a Globalized World”

Our March 6th event featured Dr. Mark Turin’s “Rising Voices: Linguistic Diversity in a Globalized World”. It was well-attended despite the sleet and cold weather, with approximately 50 people in attendance, including both the Cultural Attaché and the Education Officer from the Consulate General of Italy in Vancouver. Our reception was deliciously catered by ARPICO.

Dr. Turin’s presentation was informative, engaging, and poignant. Linguistic diversity is under extraordinary stress given that approximately 50% of the world’s 7000 living languages will cease to be spoken by the end of the century. Both linguistic and cultural diversity are being transformed through assimilation to more dominant ways of life as rapid socio-economic change and globalization exert complex pressures on small communities.

The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2019 to be the International Year of Indigenous Languages in order to help protect and promote indigenous languages. While this declaration is not a solution, it does acknowledge the precarious situation of many of the world’s languages.

According to UNESCO, 97% of the world’s people speak only 4% of the world’s languages. Local languages serve as vehicles for the transmission of both cultural heritage and unique traditional knowledge that become at risk of extinction when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted. As populations learn more dominant languages at the expense of local languages, communities undergo “language shift” and many of these local languages subsequently become at risk of linguicide: when a language dies as a result of the cessation of intergeneral transmission.

Frequently, linguicide will frequently occur when younger generations enroll in state-run schools where classes are taught in the national language(s) as opposed to the local one, serving as a tool - unintended or not - of alienation. Local, ancestral languages become sources of shame as they symbolize agrarian roots, arguably humbler origins than those of many city dwellers, and more generally, the past. The most obvious way to counter these effects is to teach in local languages as opposed to or in addition to national language(s). A less obvious but equally important countermeasure is to restructure the curricula to incorporate more locally relevant and important concepts. For example, using locally relevant occupations such as “farmer” or “shaman” when teaching maths, languages, science, etc.

Many of these local languages are spoken in areas of extraordinary biodiversity. In fact, there is a strong correlation between biodiversity and both cultural and linguistic diversity. For example, 1 in every 6 languages in spoken in the Himalayan Mountain Chain. Additionally, there is more linguistic variation in areas where local populations do not express any affiliation to mainstream religions.

Dr. Turin’s own research was used as a case study for these claims. He spent a decade learning and creating a dictionary for the Thami language, with the help and cooperation of the local community. The Thami people (known locally as Thangmi) are an indigenous community located east of Kathmandu, and have an approximate population of 30 000 people. The most common local occupation is stone quarrying . Prior to Dr. Turin’s time there, the Thami language had no written form. Today, it uses the Nepalese alphabet for the sake of ease. Following Dr. Turin’s publishing of the first English-Thami dictionary, the local community published their own trilingual (Thami, Nepalese, and English) dictionary, and subsequently, the first dictionary solely in the Thami language. Books have since been published in Thami locally, and Nepalese academic curricula has been made locally relevant and then published in Thami. As a result, more Thami children enroll and remain in school.

Why do indigenous languages matter when the main goal of language is to be understood? They matter for many reasons. As we have learned, culture and traditional knowledge is passed through these languages, and many things and concepts do not have literal/direct translations in other languages. Additionally, when indigenous communities maintain their local languages, we see suicide rates disappear. This apparent causal link is because these languages signify close-knit community ties and high rates of a sense of belonging.

ARPICO and LAURA LYNCH PRESENT:

ARPICO and LAURA LYNCH PRESENT:

ARPICO and PROF. DOUW STEYN PRESENT:

ARPICO and PROF. DOUW STEYN PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and PHILIPPE TORTELL PRESENT:

ARPICO and PHILIPPE TORTELL PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and Andrea Calì PRESENT:

ARPICO and Andrea Calì PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

ARPICO and The Consulate General of Italy PRESENT:

Since antiquity, people have been trying to answer why Rome succeeded in creating the ancient world’s largest empire. In this talk, Prof. De Angelis argues that current approaches to this question have limitations, and that room for new research exists. His approach considers the crucial eight centuries in Italy and the western Mediterranean before the Roman Empire’s creation. These centuries witnessed migrant Greeks and Phoenicians settling alongside Romans, Etruscans, and other existing populations and led to an immensely competitive environment. Societies were forced either to innovate and out-perform their competitors or to succumb to them.…

Since antiquity, people have been trying to answer why Rome succeeded in creating the ancient world’s largest empire. In this talk, Prof. De Angelis argues that current approaches to this question have limitations, and that room for new research exists. His approach considers the crucial eight centuries in Italy and the western Mediterranean before the Roman Empire’s creation. These centuries witnessed migrant Greeks and Phoenicians settling alongside Romans, Etruscans, and other existing populations and led to an immensely competitive environment. Societies were forced either to innovate and out-perform their competitors or to succumb to them.…

The vascular system is one of the first to develop during embryo development and is essential for the maintenance and function of all organs and tissues in our body. A complex network of arteries, veins, and capillaries is formed early on and further organized to supply tissues and organs with oxygen, nutrients, and other essential molecules.

The vascular system is one of the first to develop during embryo development and is essential for the maintenance and function of all organs and tissues in our body. A complex network of arteries, veins, and capillaries is formed early on and further organized to supply tissues and organs with oxygen, nutrients, and other essential molecules.

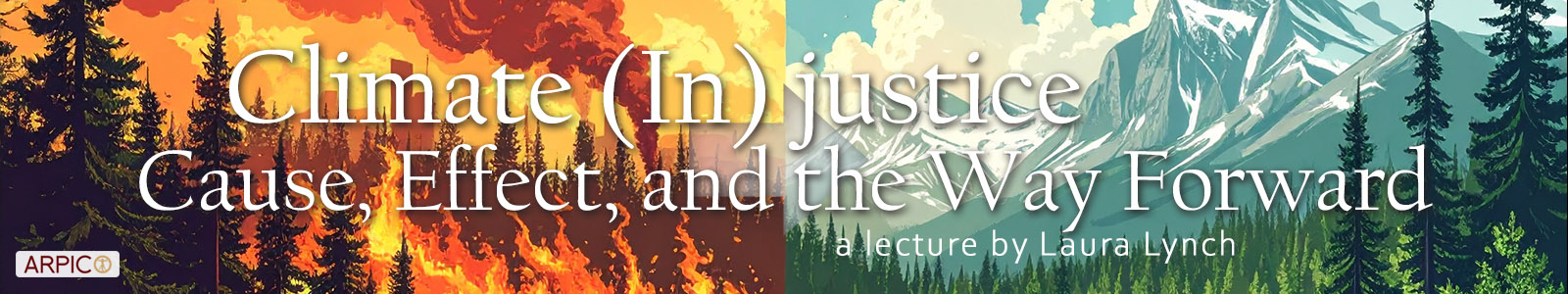

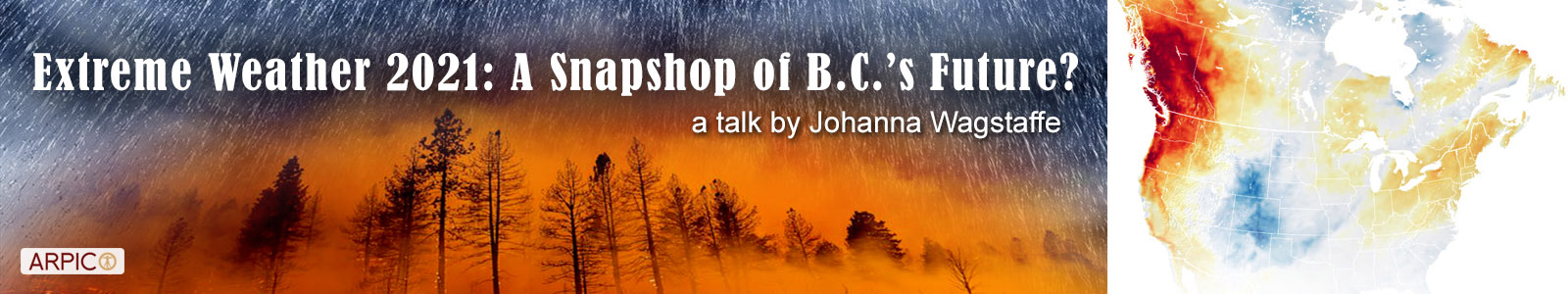

It started with a deadly heat dome that settled over the Pacific Northwest back in June 2021. That was followed by a devastating wildfire season, and that was followed by one of the worst flood disasters this province has ever seen. I'll take you through the series of unique conditions that came together for these unprecedented events to occur -- and why we need to prepare now for the next one.

It started with a deadly heat dome that settled over the Pacific Northwest back in June 2021. That was followed by a devastating wildfire season, and that was followed by one of the worst flood disasters this province has ever seen. I'll take you through the series of unique conditions that came together for these unprecedented events to occur -- and why we need to prepare now for the next one.

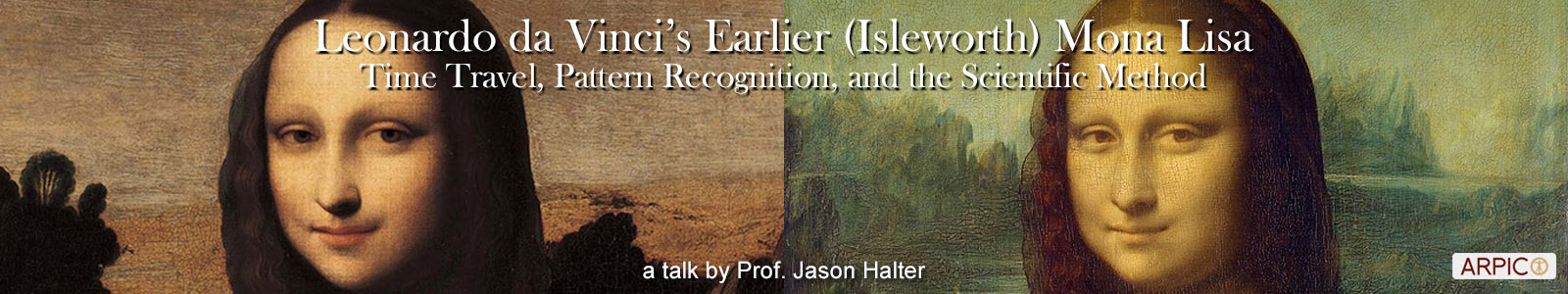

A fascinating presentation and discussion of Da Vinci’s Earlier Mona Lisa in the context of the paper of the same title that was published in Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa: New Perspectives, by Jean-Pierre Isbouts (Ed).

A fascinating presentation and discussion of Da Vinci’s Earlier Mona Lisa in the context of the paper of the same title that was published in Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa: New Perspectives, by Jean-Pierre Isbouts (Ed).

Due primarily to wolf predation on livestock (depredation), some groups oppose wolf (Canis lupus) conservation, which is an objective for large sectors of the public. Prof. Musiani's talk will compare wolf depredation of sheep in Southern Europe to wolf depredation of beef cattle in the US and Canada, taking into account the differences in social and economic contexts. It will detail where and when wolf attacks happen, and what environmental factors promote such attacks.

Due primarily to wolf predation on livestock (depredation), some groups oppose wolf (Canis lupus) conservation, which is an objective for large sectors of the public. Prof. Musiani's talk will compare wolf depredation of sheep in Southern Europe to wolf depredation of beef cattle in the US and Canada, taking into account the differences in social and economic contexts. It will detail where and when wolf attacks happen, and what environmental factors promote such attacks.

Since early 2020, we have found ourselves very focused on “the numbers” of the pandemic: counts of cases, hospitalizations and mortality; estimates of rates of spread and the effects of physical distancing policies. More recently, we have heard about the effectiveness of vaccines and how these might influence strategies for vaccine deployment. In this talk, Prof. Coombs will - in plain language - outline some of the most important quantitative concepts of epidemiology, explain their relevance to understanding the pandemic from last year to the present day, and describe how they can help us project…

Since early 2020, we have found ourselves very focused on “the numbers” of the pandemic: counts of cases, hospitalizations and mortality; estimates of rates of spread and the effects of physical distancing policies. More recently, we have heard about the effectiveness of vaccines and how these might influence strategies for vaccine deployment. In this talk, Prof. Coombs will - in plain language - outline some of the most important quantitative concepts of epidemiology, explain their relevance to understanding the pandemic from last year to the present day, and describe how they can help us project…

Eye-tracking has been extensively used both in psychology for understanding various aspects of human cognition, as well as in human computer interaction (HCI) for evaluation of interface design or as a form of direct input. In recent years, eye-tracking has also been investigated as a source of information for machine learning models that predict relevant user states and traits (e.g., attention, confusion, learning, perceptual abilities). These predictions can then be leveraged by AI agents to personalize the interaction with their users. In this talk, I will provide an overview of the research my lab has…

Eye-tracking has been extensively used both in psychology for understanding various aspects of human cognition, as well as in human computer interaction (HCI) for evaluation of interface design or as a form of direct input. In recent years, eye-tracking has also been investigated as a source of information for machine learning models that predict relevant user states and traits (e.g., attention, confusion, learning, perceptual abilities). These predictions can then be leveraged by AI agents to personalize the interaction with their users. In this talk, I will provide an overview of the research my lab has…

Whether we pick up an old-fashioned newspaper, listen to the news on the radio, or get our local or international affairs update through social media, we realize that the state of the economy at pretty much all scales is lurking behind many aspects of our lives and may be responsible for their ups and downs. The intricacies linking trade and economics with politics especially at the international level can be tricky to unravel. We are therefore fortunate to have professor Matilde Bombardini from UBC come and enlighten us on these very timely topics.

Whether we pick up an old-fashioned newspaper, listen to the news on the radio, or get our local or international affairs update through social media, we realize that the state of the economy at pretty much all scales is lurking behind many aspects of our lives and may be responsible for their ups and downs. The intricacies linking trade and economics with politics especially at the international level can be tricky to unravel. We are therefore fortunate to have professor Matilde Bombardini from UBC come and enlighten us on these very timely topics.

ARPICO is proud to host UBC anthropologist, Dr. Sabina Magliocco, who will share her presentation of Modern Pagan Religions with us. This presentation examines modern Paganisms, a group of new religions that revive, reimagine, and experiment with elements of pre-Christian worship. Emerging in the middle of the 20th century, as many established religions began to lose members, they seek to re-enchant a disenchanted world and forge stronger connections to the sacred through nature and community. These new religious movements are countercultural, in that they construct identities in opposition to the dominant religious paradigm; yet at…

ARPICO is proud to host UBC anthropologist, Dr. Sabina Magliocco, who will share her presentation of Modern Pagan Religions with us. This presentation examines modern Paganisms, a group of new religions that revive, reimagine, and experiment with elements of pre-Christian worship. Emerging in the middle of the 20th century, as many established religions began to lose members, they seek to re-enchant a disenchanted world and forge stronger connections to the sacred through nature and community. These new religious movements are countercultural, in that they construct identities in opposition to the dominant religious paradigm; yet at…

ARPICO is proud to host Dr. Silvia Scorza, who will be presenting on the topic of underground science at SNOLAB, where research is conducted in fields of fundamental science that require shielding from external radiation such as cosmic rays. This presentation will give a unique and interesting perspective into the research that is conducted mostly out of the public view and discussion, but contributes critically to our scientific advances. Applications found in medicine, nat

ARPICO is proud to host Dr. Silvia Scorza, who will be presenting on the topic of underground science at SNOLAB, where research is conducted in fields of fundamental science that require shielding from external radiation such as cosmic rays. This presentation will give a unique and interesting perspective into the research that is conducted mostly out of the public view and discussion, but contributes critically to our scientific advances. Applications found in medicine, nat

The ancient Romans believed that a healthy body and mind go hand in hand: mens sana in corpore sano! During the American Civil War physicians described the Soldier’s Heart as a syndrome that occurred on the battlefield that involved symptoms very similar to modern day posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They also noted that these soldiers manifested exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and “abnormalities of the heart”. Interventions were developed to reduce the damage on the cardiovascular system and included surgical interventions to neutralize the sympathetic nervous system hyper-activity. With the advent of modern psychoanalysis, psychiatric symptoms became…

The ancient Romans believed that a healthy body and mind go hand in hand: mens sana in corpore sano! During the American Civil War physicians described the Soldier’s Heart as a syndrome that occurred on the battlefield that involved symptoms very similar to modern day posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They also noted that these soldiers manifested exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and “abnormalities of the heart”. Interventions were developed to reduce the damage on the cardiovascular system and included surgical interventions to neutralize the sympathetic nervous system hyper-activity. With the advent of modern psychoanalysis, psychiatric symptoms became…

Understanding the true nature of our universe is one of the most fundamental quests of our society. The path of knowledge acquisition in that quest has led us to the hypothesis of "dark matter", that is, a large proportion of the mass of the universe which appears invisible. In this lecture, with minimal technical language we will journey through the structure and evolution of the universe, from subatomic particles to the big bang, which gave rise to our universe, in an ultimate research to describe the dark side of the universe called dark matter. We…

Understanding the true nature of our universe is one of the most fundamental quests of our society. The path of knowledge acquisition in that quest has led us to the hypothesis of "dark matter", that is, a large proportion of the mass of the universe which appears invisible. In this lecture, with minimal technical language we will journey through the structure and evolution of the universe, from subatomic particles to the big bang, which gave rise to our universe, in an ultimate research to describe the dark side of the universe called dark matter. We…

In this lecture we will explore a part of our food system, which has received much press, but which consumers still misunderstand: food derived from biotechnology often referred to as genetically modified organisms. We will be learning about the types of plants and animals which are genetically engineered and part of our everyday food system and the reasons for which they have been transformed genetically. We will be looking at the issue from several different angles. You are encouraged to approach the topic with an open mind, and learn how the technology is being used.…

In this lecture we will explore a part of our food system, which has received much press, but which consumers still misunderstand: food derived from biotechnology often referred to as genetically modified organisms. We will be learning about the types of plants and animals which are genetically engineered and part of our everyday food system and the reasons for which they have been transformed genetically. We will be looking at the issue from several different angles. You are encouraged to approach the topic with an open mind, and learn how the technology is being used.…

ARPICO presents: The 2018 AGM of ARPICO will take place on June 4th, 2016 at 6:00PM at the Italian Cultural Center in the Museum & Art Gallery.

ARPICO presents: The 2018 AGM of ARPICO will take place on June 4th, 2016 at 6:00PM at the Italian Cultural Center in the Museum & Art Gallery.

Brain illness, comprising neurological disorders, mental illness and addiction, is considered the major health challenge in the 21st century with a socio-economic cost greater than cancer and cardiovascular disease combined. There are at least three unique challenges hampering brain disease management: relative inaccessibility, disease onset often preceding the onset of clinical symptoms by many years and overlap between clinical and pathological symptoms that makes accurate disease identification often difficult. This talk will give examples of how positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has contributed to better understanding of the brain function and disease with particular focus…

Brain illness, comprising neurological disorders, mental illness and addiction, is considered the major health challenge in the 21st century with a socio-economic cost greater than cancer and cardiovascular disease combined. There are at least three unique challenges hampering brain disease management: relative inaccessibility, disease onset often preceding the onset of clinical symptoms by many years and overlap between clinical and pathological symptoms that makes accurate disease identification often difficult. This talk will give examples of how positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has contributed to better understanding of the brain function and disease with particular focus…

The so-called “myth of secularization” held that, with standards of living and education levels rising around the world, traditional religious beliefs and affiliations would eventually fade away. More and more people, it was thought, would join the West in its state of living without supernatural commitments or ancient superstitions, guided solely by rationality, empirical evidence and enlightened self-interest. This myth appears to be mistaken on at least two fronts. To begin with, religiosity has by no means faded away. In some regions of the world levels of religiosity have risen dramatically, and in many places…

The so-called “myth of secularization” held that, with standards of living and education levels rising around the world, traditional religious beliefs and affiliations would eventually fade away. More and more people, it was thought, would join the West in its state of living without supernatural commitments or ancient superstitions, guided solely by rationality, empirical evidence and enlightened self-interest. This myth appears to be mistaken on at least two fronts. To begin with, religiosity has by no means faded away. In some regions of the world levels of religiosity have risen dramatically, and in many places…

ARPICO presents:

ARPICO presents:

Cancer has now become the most common cause of death. While not the biggest killer of men, the most common potentially lethal cancer to afflict males is cancer of the prostate, accounting for over 20% of all cancers in this group. In fact, 1 in 7 men will develop prostate cancer some time in their lifetime. The presentation will deal with prevalence of prostate cancer, possible genetic and other links as causes of this cancer, what you can do to protect yourself from this disease, how it is diagnosed (PSA and other diagnostic measures), how…

Cancer has now become the most common cause of death. While not the biggest killer of men, the most common potentially lethal cancer to afflict males is cancer of the prostate, accounting for over 20% of all cancers in this group. In fact, 1 in 7 men will develop prostate cancer some time in their lifetime. The presentation will deal with prevalence of prostate cancer, possible genetic and other links as causes of this cancer, what you can do to protect yourself from this disease, how it is diagnosed (PSA and other diagnostic measures), how…

We have the good fortune of living in a beautful corner of the planet where spectacular coast mountain scenery borders the temperate Pacific Ocean. But this priviledge comes at a price. The same forces that lift the coast mountains from the sea are responsible for one of the most powerful of natural disasters: earthquakes. In this talk, I will discuss several distinct classes of earthquake that occur in the Pacific Northwest and the seismic hazard they pose. This list includes the highly anticipated magnitude 9 "megathrust" event that will rupture the entire Cascadia plate…

We have the good fortune of living in a beautful corner of the planet where spectacular coast mountain scenery borders the temperate Pacific Ocean. But this priviledge comes at a price. The same forces that lift the coast mountains from the sea are responsible for one of the most powerful of natural disasters: earthquakes. In this talk, I will discuss several distinct classes of earthquake that occur in the Pacific Northwest and the seismic hazard they pose. This list includes the highly anticipated magnitude 9 "megathrust" event that will rupture the entire Cascadia plate…

It is now 35 years since the discovery of AIDS but its origins continue to be puzzling. Looking back to the early 20th-century events in Africa, scientists traced the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic from its transmission from chimpanzees to man, and uncovered how colonial medical campaigns to eradicate tropical diseases started the spread of the virus, and how urbanization and prostitution had a disastrous effect later on to amplify the epidemic from West Africa to Kinshasa, then to the rest of Africa, to Haiti and ultimately worldwide.

It is now 35 years since the discovery of AIDS but its origins continue to be puzzling. Looking back to the early 20th-century events in Africa, scientists traced the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic from its transmission from chimpanzees to man, and uncovered how colonial medical campaigns to eradicate tropical diseases started the spread of the virus, and how urbanization and prostitution had a disastrous effect later on to amplify the epidemic from West Africa to Kinshasa, then to the rest of Africa, to Haiti and ultimately worldwide.

ARPICO presents:

The 2016 AGM of ARPICO will take place on May 31st, 2016 at 5:30PM at the Roundhouse Community Centre, Room B.

ARPICO presents:

The 2016 AGM of ARPICO will take place on May 31st, 2016 at 5:30PM at the Roundhouse Community Centre, Room B.

Patrick Walden graduated with a B.Sc. in Physics from UBC and a Ph.D in Particle Physics from Caltech. His Post Doctoral research was done at the Stanford University Linear Accelerator (SLAC), and since 1974 he has been at TRIUMF here in Vancouver. Patrick has been active in the fields of pion photo-production, meson spectroscopy, the dynamics of pion production from nuclei, and nuclear astrophysics. Nuclear power is the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions-free energy in the world. It supplies approximately 5% of the world's total energy demand. Presently, human activity is on the brink of initiating…

Patrick Walden graduated with a B.Sc. in Physics from UBC and a Ph.D in Particle Physics from Caltech. His Post Doctoral research was done at the Stanford University Linear Accelerator (SLAC), and since 1974 he has been at TRIUMF here in Vancouver. Patrick has been active in the fields of pion photo-production, meson spectroscopy, the dynamics of pion production from nuclei, and nuclear astrophysics. Nuclear power is the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions-free energy in the world. It supplies approximately 5% of the world's total energy demand. Presently, human activity is on the brink of initiating…

Christopher McPherson, senior prosecutor with the Ministry of Justice, Province of British Columbia, is responsible for challenging high-profile homicide cases. He has prosecuted over 30 homicide cases. Elected a Bencher for 2016, Christopher is a member of the Discipline Committee and Equity and Diversity Advisory Committee. Christopher has served as a director of the BC Crown Counsel Association, and is a member of the International Association of Prosecutors and International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law. His teaching and lecturing experience includes coach of the Western Canadian Criminal Moot Competition and UBC Burns Moot Competition, instructor…

Christopher McPherson, senior prosecutor with the Ministry of Justice, Province of British Columbia, is responsible for challenging high-profile homicide cases. He has prosecuted over 30 homicide cases. Elected a Bencher for 2016, Christopher is a member of the Discipline Committee and Equity and Diversity Advisory Committee. Christopher has served as a director of the BC Crown Counsel Association, and is a member of the International Association of Prosecutors and International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law. His teaching and lecturing experience includes coach of the Western Canadian Criminal Moot Competition and UBC Burns Moot Competition, instructor…

Dr. Arianna Dagnino is a researcher, writer, and socio-cultural analyst. She holds a M.A. in Modern Foreign Languages and Literatures from l'Università degli Studi di Genova and a Ph.D. in Sociology and Comparative Literature from the University of South Australia. She currently teaches at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Global cities such as Vancouver, London, Berlin or Sydney currently face two major problems: house affordability and the risk of highly fragmented societies across cultural lines.

In her talk, Dr. Dagnino argues that one of the possible solutions to address the negative aspects of economic globalization…

Dr. Arianna Dagnino is a researcher, writer, and socio-cultural analyst. She holds a M.A. in Modern Foreign Languages and Literatures from l'Università degli Studi di Genova and a Ph.D. in Sociology and Comparative Literature from the University of South Australia. She currently teaches at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Global cities such as Vancouver, London, Berlin or Sydney currently face two major problems: house affordability and the risk of highly fragmented societies across cultural lines.

In her talk, Dr. Dagnino argues that one of the possible solutions to address the negative aspects of economic globalization… ARPICO presents:

Please join us in celebrating the holidays and another wonderful year at our annual Christmas Dinner at Marcello's Pizzeria.

ARPICO presents:

Please join us in celebrating the holidays and another wonderful year at our annual Christmas Dinner at Marcello's Pizzeria.

Prof. Douw Steyn, PhD, ACM, FCMOS, is Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science at The University of British Columbia, in the Department of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences. He is a member of the Institute for Applied Mathematics, the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, and the Liu Institute for Global Issues. He has served as Associate Dean (Research and Faculty Development) in the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Principal of the College for Interdisciplinary Studies.

Prof. Steyn's professional, teaching and research activities are in the field of air pollution meteorology, boundary layer meteorology, mesoscale meteorology, environmental science…

Prof. Douw Steyn, PhD, ACM, FCMOS, is Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science at The University of British Columbia, in the Department of Earth Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences. He is a member of the Institute for Applied Mathematics, the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, and the Liu Institute for Global Issues. He has served as Associate Dean (Research and Faculty Development) in the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Principal of the College for Interdisciplinary Studies.

Prof. Steyn's professional, teaching and research activities are in the field of air pollution meteorology, boundary layer meteorology, mesoscale meteorology, environmental science…

ARPICO is pleased to invite you to the informal dinner on August 22 in honor of Anadi Canepa, our president of four years, who will be leaving Vancouver the end of August to accept a position as a research scientist with a most prestigious research facility, Fermi Lab-Chicago, USA.

ARPICO is pleased to invite you to the informal dinner on August 22 in honor of Anadi Canepa, our president of four years, who will be leaving Vancouver the end of August to accept a position as a research scientist with a most prestigious research facility, Fermi Lab-Chicago, USA.

Prof. Samoil Bilenky will introduce a movie on the life of Bruno Pontecorvo

The movie will trace the main points of Bruno Pontecorvo's life, a nuclear physicist, who was born in 1913 in Pisa, Italy, and died in 1993 in Dubna, Russia.

Samoil Bilenky worked with Pontecorvo from 1975 until 1989 in Dubna where they developed the theory of neutrino masses and oscillations, and proposed experiments on the search for neutrino oscillations.

The impact of Bruno Pontecorvo on neutrino physics is well recognized in the Scientific World.

Prof. Samoil Bilenky will introduce a movie on the life of Bruno Pontecorvo

The movie will trace the main points of Bruno Pontecorvo's life, a nuclear physicist, who was born in 1913 in Pisa, Italy, and died in 1993 in Dubna, Russia.

Samoil Bilenky worked with Pontecorvo from 1975 until 1989 in Dubna where they developed the theory of neutrino masses and oscillations, and proposed experiments on the search for neutrino oscillations.

The impact of Bruno Pontecorvo on neutrino physics is well recognized in the Scientific World.

Dr. John J. Spinelli is a Distinguished Scientist and Head of Cancer Control Research at the BC Cancer Agency, Professor at the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science at Simon Fraser University. He is the principal investigator for the BC Generations Project, part of the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project, the largest health study ever undertaken in Canada.

Dr. Spinelli's primary research focus is on the identification of environmental and genetic risk factors for cancer and in the interaction between…

Dr. John J. Spinelli is a Distinguished Scientist and Head of Cancer Control Research at the BC Cancer Agency, Professor at the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science at Simon Fraser University. He is the principal investigator for the BC Generations Project, part of the Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow Project, the largest health study ever undertaken in Canada.

Dr. Spinelli's primary research focus is on the identification of environmental and genetic risk factors for cancer and in the interaction between…

Dr. Francesco Berna is Assistant Professor at Simon Fraser University's Department of Archaeology, where he teaches introductory and advanced courses in archaeology. Born in Rome, he graduated from the University of Florence, where he also obtained his PhD. The main focus of his research is on the origin of modern behaviour and the onset of the controlled use of fire during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

The biology, diet, habitat, and behavior of our species are deeply entangled with the use of fire to the point that our survival is,…

Dr. Francesco Berna is Assistant Professor at Simon Fraser University's Department of Archaeology, where he teaches introductory and advanced courses in archaeology. Born in Rome, he graduated from the University of Florence, where he also obtained his PhD. The main focus of his research is on the origin of modern behaviour and the onset of the controlled use of fire during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

The biology, diet, habitat, and behavior of our species are deeply entangled with the use of fire to the point that our survival is,…

Arianna Dagnino holds a PhD in comparative literature from the University of South Australia and a Masters Degree in foreign languages from the University of Genoa. In the last 25 years she has lived across four continents, writing more than 700 articles for the italian press. She has published a transcultural novel, Fossili (Rome: Fazi, 2010), inspired by her four years in South Africa, and several books on the impact of socio-techno globalization. Dagnino is also an ethnographic researcher working with the international research centre Future Concept Lab (

Arianna Dagnino holds a PhD in comparative literature from the University of South Australia and a Masters Degree in foreign languages from the University of Genoa. In the last 25 years she has lived across four continents, writing more than 700 articles for the italian press. She has published a transcultural novel, Fossili (Rome: Fazi, 2010), inspired by her four years in South Africa, and several books on the impact of socio-techno globalization. Dagnino is also an ethnographic researcher working with the international research centre Future Concept Lab (

Federico Rosei has held the Canada Research Chair in Nanostructured Organic and Inorganic Materials since 2003. He is Professor and Director of Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique, Énergie, Matériaux et Télécommunications, Université du Québec, Varennes (QC) Canada. Since January 2014 he holds the UNESCO Chair in Materials and Technologies for Energy Conversion, Saving and Storage. He received MSc and PhD degrees from the University of Rome "La Sapienza" in 1996 and 2001, respectively.

Federico Rosei has held the Canada Research Chair in Nanostructured Organic and Inorganic Materials since 2003. He is Professor and Director of Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique, Énergie, Matériaux et Télécommunications, Université du Québec, Varennes (QC) Canada. Since January 2014 he holds the UNESCO Chair in Materials and Technologies for Energy Conversion, Saving and Storage. He received MSc and PhD degrees from the University of Rome "La Sapienza" in 1996 and 2001, respectively.

Steno Ferluga, who will give a talk about Hack's career and life, was a pupil of Margherita Hack and then became a coworker of hers as well as a personal friend. He now teaches Environmental Physics at the University of Udine.

On June 29, 2013, Margherita Hack passed away at the age of 91. Hack was an eminent astrophysicist, as well as a popular science writer, very well known in Italy and abroad for her professional achievements but also for her personal choices and opinions. A staunch vegetarian and a convinced atheist, Hack directed the Trieste Astronomical…

Steno Ferluga, who will give a talk about Hack's career and life, was a pupil of Margherita Hack and then became a coworker of hers as well as a personal friend. He now teaches Environmental Physics at the University of Udine.

On June 29, 2013, Margherita Hack passed away at the age of 91. Hack was an eminent astrophysicist, as well as a popular science writer, very well known in Italy and abroad for her professional achievements but also for her personal choices and opinions. A staunch vegetarian and a convinced atheist, Hack directed the Trieste Astronomical…

Dr Schaffer is responsible for maintaining the medical isotope and radiotracer production programs at TRIUMF, in support of neurology and oncology research. For his leadership in the field, Dr Schaffer was recently recognized as one of BC's Top Forty under 40 by Business in Vancouver magazine. He continues to re-define the TRIUMF nuclear medicine program as a leader, an entrepreneur and one of British Columbia's most promising scientific talents. A modest man with a sense of humour and a strong commitment to his family and playing hard outdoors, Paul came to TRIUMF in 2009 from the private…

Dr Schaffer is responsible for maintaining the medical isotope and radiotracer production programs at TRIUMF, in support of neurology and oncology research. For his leadership in the field, Dr Schaffer was recently recognized as one of BC's Top Forty under 40 by Business in Vancouver magazine. He continues to re-define the TRIUMF nuclear medicine program as a leader, an entrepreneur and one of British Columbia's most promising scientific talents. A modest man with a sense of humour and a strong commitment to his family and playing hard outdoors, Paul came to TRIUMF in 2009 from the private…

Dr. Matthews is Mission Scientist leading the Canadian Space Agency's MOST project, and a Professor of Astrophysics in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at the University of British Columbia. Prof. Matthews is a world-leading expert in the fields of stellar seismology, exoplanetary science, and astronomical instrumentation and time series analysis. Prof. Matthews' media adventures include frequent appearances on CBC TV and Radio, CTV, Global, CNN, CityTV, The Knowledge Network, Shaw TV, and Space: The Imagination Station, as well as playing himself ("Jaymie" Rocket Scientist) in a national Fountain Tire television ad campaign. Dr. Matthews posed in…

Dr. Matthews is Mission Scientist leading the Canadian Space Agency's MOST project, and a Professor of Astrophysics in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at the University of British Columbia. Prof. Matthews is a world-leading expert in the fields of stellar seismology, exoplanetary science, and astronomical instrumentation and time series analysis. Prof. Matthews' media adventures include frequent appearances on CBC TV and Radio, CTV, Global, CNN, CityTV, The Knowledge Network, Shaw TV, and Space: The Imagination Station, as well as playing himself ("Jaymie" Rocket Scientist) in a national Fountain Tire television ad campaign. Dr. Matthews posed in…

Marco Ciufolini (b. Rome; B.S., Spring Hill College; Ph.D., Michigan; Postdoc 1982-84, Yale) has held academic positions at Rice University (1984-98), the University of Lyon (1998-2004), and UBC (2004-present), where he is the Canada Research Chair in Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

The Istituto teams up once again with ARPICO, the Society on of Italian Researchers and Professionals of Western Canada, to present a fascinating talk celebrating the 50th anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Prize to Italian scientist Giulio Natta. Organic chemistry, the branch of chemical science that focuses on carbon-based materials, permits the conversion of basic…

Marco Ciufolini (b. Rome; B.S., Spring Hill College; Ph.D., Michigan; Postdoc 1982-84, Yale) has held academic positions at Rice University (1984-98), the University of Lyon (1998-2004), and UBC (2004-present), where he is the Canada Research Chair in Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

The Istituto teams up once again with ARPICO, the Society on of Italian Researchers and Professionals of Western Canada, to present a fascinating talk celebrating the 50th anniversary of the awarding of the Nobel Prize to Italian scientist Giulio Natta. Organic chemistry, the branch of chemical science that focuses on carbon-based materials, permits the conversion of basic…

Prof. Fabio Rossi & Video Interview with Rita Levi-Montalcini

On December 30, 2012, Italy lost one of its most prestigious minds in the scientific domain: neuro-biologist Rita Levi-Montalcini, who passed away at the age of 103. Together with colleague Stanley Cohen, Levi-Montalcini was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of nerve growth factor. The Istituto Italiano di Cultura, in collaboration with ARPICO - the Association of Italian Researchers and Professionals of Western Canada -, presents an evening commemorating the life and achievements of this outstanding scientist, who famously had to conduct…

Prof. Fabio Rossi & Video Interview with Rita Levi-Montalcini

On December 30, 2012, Italy lost one of its most prestigious minds in the scientific domain: neuro-biologist Rita Levi-Montalcini, who passed away at the age of 103. Together with colleague Stanley Cohen, Levi-Montalcini was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of nerve growth factor. The Istituto Italiano di Cultura, in collaboration with ARPICO - the Association of Italian Researchers and Professionals of Western Canada -, presents an evening commemorating the life and achievements of this outstanding scientist, who famously had to conduct…

Particle Physicist "Nephew of Emilio Segre, winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize for the discovery of the antiproton". Born in Florence, Italy in 1938, Gino Segre grew up in New York and Italy. He graduated from Harvard University (A.B., 1959) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Ph.D., 1963). He is now a professor emeritus in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. He has been a visiting professor at M.I.T and at Oxford University as well as a visiting Fellow at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) and the University of California,…

Particle Physicist "Nephew of Emilio Segre, winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize for the discovery of the antiproton". Born in Florence, Italy in 1938, Gino Segre grew up in New York and Italy. He graduated from Harvard University (A.B., 1959) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Ph.D., 1963). He is now a professor emeritus in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. He has been a visiting professor at M.I.T and at Oxford University as well as a visiting Fellow at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) and the University of California,…

Alberto Angela is a paleontologist, science writer, author, and italian journalist.

This fascinating documentary illustrates Italy's major recent achievements in the field of science and technology, achievements that will have significant consequences at a global level in the years to come - like the iCub robot, who is capable of learning from experience. Filmed in the beautiful setting of Rome's Centrale Montemartini - the new exhibition space for the Musei Capitolini, in the former "Giovanni Montemartini Thermoelectric Centre", an extraordinary example of industrial archaeology converted into a museum -, the documentary is presented by Alberto Angela and…

Alberto Angela is a paleontologist, science writer, author, and italian journalist.

This fascinating documentary illustrates Italy's major recent achievements in the field of science and technology, achievements that will have significant consequences at a global level in the years to come - like the iCub robot, who is capable of learning from experience. Filmed in the beautiful setting of Rome's Centrale Montemartini - the new exhibition space for the Musei Capitolini, in the former "Giovanni Montemartini Thermoelectric Centre", an extraordinary example of industrial archaeology converted into a museum -, the documentary is presented by Alberto Angela and…

Prof. Luciana Duranti, Chair and Professor School of Library, Archivial and Information Studies, University of British Columbia Trust has been defined in many ways, but, at its core, it involves acting without the knowledge needed to act. It consists of substituting the information that one does not have with other information. For example, a person who does not have the knowledge necessary to assess the authenticity of a record relies on the credentials of the expert who authenticates it. Individuals and organizations are increasingly saving and accessing records in the highly networked, easily hacked environment of the Internet.…

Prof. Luciana Duranti, Chair and Professor School of Library, Archivial and Information Studies, University of British Columbia Trust has been defined in many ways, but, at its core, it involves acting without the knowledge needed to act. It consists of substituting the information that one does not have with other information. For example, a person who does not have the knowledge necessary to assess the authenticity of a record relies on the credentials of the expert who authenticates it. Individuals and organizations are increasingly saving and accessing records in the highly networked, easily hacked environment of the Internet.…

A former Pisa scholar, Sergio Bertolucci has worked at DESY, Fermilab and Frascati. He was appointed head of the Frascati National Laboratories accelerator division becoming Director in 2002. Before taking over the Directorate for Research at CERN, Bertolucci was already chairing the LHC committee and was a member of DESY's physics research committee. He was also vice-president and a member of the Board of the Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics.

Bertolucci will talk about the investigation of the deepest-held mysteries of our universe at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) of CERN. "The LHC is probably the…

A former Pisa scholar, Sergio Bertolucci has worked at DESY, Fermilab and Frascati. He was appointed head of the Frascati National Laboratories accelerator division becoming Director in 2002. Before taking over the Directorate for Research at CERN, Bertolucci was already chairing the LHC committee and was a member of DESY's physics research committee. He was also vice-president and a member of the Board of the Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics.

Bertolucci will talk about the investigation of the deepest-held mysteries of our universe at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) of CERN. "The LHC is probably the…

Dr. John Robinson, executive Director of the UBC Sustainability Initiative Professor with the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability, and the Department of Geography, at the University of British Columbia.

The Greenest City Conservations (GCC) project is aimed at testing multiple channels for public engagement on sustainability policies. Its two main goals are (1) to facilitate discussion, solicit and analyze public attitudes and opinions on, and support for, a variety of sustainability policies; and (2) to provide a comprehensive understanding of the content and impacts (both qualitative and quantitative) of six different modes of public engagement ("channels"):…

Dr. John Robinson, executive Director of the UBC Sustainability Initiative Professor with the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability, and the Department of Geography, at the University of British Columbia.

The Greenest City Conservations (GCC) project is aimed at testing multiple channels for public engagement on sustainability policies. Its two main goals are (1) to facilitate discussion, solicit and analyze public attitudes and opinions on, and support for, a variety of sustainability policies; and (2) to provide a comprehensive understanding of the content and impacts (both qualitative and quantitative) of six different modes of public engagement ("channels"):…

Dr. Fabio Rossi, tenured associate professor in Medical Genetics at the University of British Columbia, member of the board of directors of the National Centres of Excellency - Stem Cell Network, and scientific advisor of Muscular Dystrophy Canada. More information about Dr. Rossi are available here:

Dr. Fabio Rossi, tenured associate professor in Medical Genetics at the University of British Columbia, member of the board of directors of the National Centres of Excellency - Stem Cell Network, and scientific advisor of Muscular Dystrophy Canada. More information about Dr. Rossi are available here: